By Heather Hausenblaus

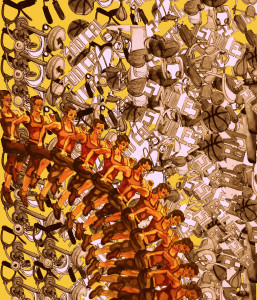

Illustrations by Amalia Galdona-Broche ‘16

Have you ever noticed an avid exerciser at your local gym — someone who is always running on the treadmill for long lengths of time or hovering around the weight room well after others have showered and gone home? Perhaps you’ve even felt lazy and out of shape by comparison, and have respected this person’s dedication and motivation.

Historically, researchers have been interested in determining the minimum amount of exercise needed to be healthy, and for good reason since most of us – approximately 80 percent – do not engage in enough exercise. However, did you ever stop to wonder whether the health nuts and gym rats of the world’s commitment to exercise might have turned into an unhealthy addiction?

When we increase our activity levels, our mental and physical health follow suit – up to a certain point, that is. When we stop taking days off from the gym or workout for longer than our bodies can handle, we impair our strength, our stamina, and our overall well-being. Some research suggests that exercise’s mental benefits max out at around 14 hours of physical activity per week. But each of us has a unique tipping point beyond which continuing to sweat, lift, burn, or push past pain does more harm than good.

Interestingly enough, the idea that people can become addicted to exercise was accidently identified by Frederick Baekeland in 1970. This often happens in research – scientists are testing a certain hypothesis and then stumble upon an intriguing concept that leads them in a different and unexpected direction.

Baekeland wanted to study the common belief that exercise promotes deep sleep by having avid runners stop running for one month and examine how it affected their sleep patterns. Two key study findings led him to the conclusion that some individuals may become addicted to physical activity.

First, he encountered great difficulty recruiting avid male exercisers – those individuals who ran almost every day – who were willing to stop running for one month, and ultimately, no amount of money was great enough to persuade those runners. Ultimately, he was able to recruit individuals who regularly ran three to four days a week.

First, he encountered great difficulty recruiting avid male exercisers – those individuals who ran almost every day – who were willing to stop running for one month, and ultimately, no amount of money was great enough to persuade those runners. Ultimately, he was able to recruit individuals who regularly ran three to four days a week.

Second, the men who took the time off from running for one month reported negative changes in their wellbeing – higher anxiety, lower libido, restlessness, and interrupted sleep. In short, he found that avid and regular runners either flatly refused to stop exercising for a one month or reported psychological stress.

Since this time, researchers have continued to shed some light on the notion that there may be a point at which too much exercise may have detrimental physical and psychological health effects and, over time, become an addiction. That said, research into exercise addiction – also referred to as exercise dependence, excessive exercise, and compulsive exercise – has seen its share of controversy. Some scientists have challenged the disorder’s validity by denying that an addictive relationship with physical activity could be unhealthy. After all, they argue, aren’t we more concerned about how many people aren’t getting to the gym at all?

Other researchers and mental health professionals debate as to whether exercise addiction is its own, separate psychological issue or whether it’s simply another iteration of an eating disorder. Indeed, excessive exercise is a prominent feature of eating disorders with more than 40% of eating disorder patients engaging in excessive exercise in an attempt to control their weight.

For clarity, a consensus has emerged distinguishing two distinct types of exercise addiction. For primary exercise addiction, the physical activity itself is the gratification-inducing end. For secondary exercise addiction, physical activity is secondary to an eating disorder and the main motivation for the extreme physical activity is to control and manipulate weight. The focus of this article is on primary exercise addiction.

How can you tell if someone may be addicted to exercise? Just because someone runs seven days a week for an hour each time or has been regularly attending fitness classes for several years does not mean that he or she is addicted to exercise. In fact, there are thousands of people who can be physically active six or even seven days a week who should not and could not be classified as an exercise addict. Addiction is indicated, not only by the behavior, but also by the psychological reasons underlying that behavior. It is the compulsive need and pathological motivation to exercise that distinguishes someone from a regular exerciser, to a highly committed exerciser, to an addicted exerciser. If a person reports feelings of anxiety and depression when unable to exercise, spends little to no time with family or friends because of physical activity involvement, and continues to exercise despite a doctor’s advice to allow an overuse injury to heal, he or she may be at high risk for exercise addiction.

• First, the exerciser continually needs to increase his or her time spent exercising or the intensity of the workout to achieve the originally desired effect, such as being in a better mood or having more energy. In other words, the amount of exercise that once sufficed no longer makes as much of a difference. This is referred to as tolerance.

• The second criterion, withdrawal, refers to negative moods that are experienced when an addict is unable to exercise. When a person can’t squeeze in his preferred running routine as planned, negative moods like anxiety, depression, and frustration often creep in. And addicts may also feel driven to exercise just to offset these negative moods.

• The third criterion, intention effects, occurs when people exercise more than they had originally intended to. An exercise addict is unable to stick to the intended time and will often exercise much longer or with a higher intensity than originally planned. Despite planning to spend only thirty minutes on the elliptical or treadmill, an overly enthusiastic exerciser might spend upward of an hour or more in motion, missing or arriving late to an important meeting or event. A weight lifter who promises to stop after three sets suddenly feels he can’t rest until he’s completed a fourth, a fifth, or a sixth.

• The fourth criterion is loss of control over the exercise behavior. The worse an exercise addict’s pathology becomes, the less of a handle he has over his thoughts, behavior, and response to the gym. Focus outside of the gym continually circles back to exercise. Thoughts race to when and how he’ll squeeze in his daily routine. Even with an awareness that his regimen may be getting a bit out of hand, the exercise addict repeatedly finds himself unable to stop or cut back. More reps are added and more calories clamor to be burned, even if he wants nothing more than to go home, take a day off, or do something sedentary. Rather than being in control of his workouts, his exercise schedule has assumed control over him.

• The fifth criterion, time, refers to the hours spent engaging in exercise or exercise-related activities. A large chunk of an exercise addict’s time during the day is devoted to physical activity. Vacations are often fitness-oriented –skiing, hiking, mountain climbing, etc. – employment may be exercise-oriented – being a physical trainer – and reading material is often fitness-related.

• The sixth criterion, conflict, refers to non-fitness related activities that fall by the wayside because they conflict with exercise. Time spent relaxing with friends or family is truncated to make more room for exercise. What once brought an exercise addict fulfillment may seem like a nuisance because it gets in the way of his or her workout.

• Finally the seventh criterion, continuance refers to continuing to exercise despite physical or psychological issues that should prevent the activity. Exercise addicts often push past pain, injury, and illness to finish a workout even against their doctor’s orders. If an exercise addict has been told they have an overuse injury, it will not stop their exercise routine. They will find another activity or push through the pain. The alternative of taking time off is not an option for an exercise addict.

It’s difficult to separate healthy exercise from obsessive exercise. Meeting some of the above criteria doesn’t necessarily mean you’re an exercise addict. A lot of people with a healthy attitude toward exercise choose to become personal trainers, work at a gym, run marathons, and even ultra-marathons. It’s when exercise becomes all consuming — when one loses friends, forgoes social activities or reneges on work opportunities — that a workout schedule becomes cause for concern. In other words, people addicted to exercise continue to keep going despite injuries, mental issues, social obligations, and physical exhaustion. They may even watch their careers crumble, and their family and friends drift away because exercise is their top – and sometimes only – priority. In other words, physical activity engulfs an exercise addict’s personal, professional, and social life, and is experienced by the addict as difficult to control or reduce in frequency — even in the face of illness or injury.

It is estimated that 0.3 percent of the total population is at risk for exercise adddiction. These research based estimates are in concordance with the argument that exercise addiction is relatively rare, especially when compared to other addictions. Still, small as this number may seem, it still translates to roughly thirty out of every ten thousand people. Given the physical and emotional consequences associated with exercise addiction, that’s no insignificant number.

Exercise addiction is a pattern of physical activity that exceeds what most fitness and medical professionals consider “normal,” causes immense psychological anguish – either during, following, or in anticipation of exercise – engulfs an exercise addict’s personal, professional, and social life, and is experienced by the addict as difficult to control or reduce in frequency. For most of us, exercise is great for the body, the soul, and the mind. But for a limited number, it can become an obsession.

Though exercise addiction still awaits inclusion in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – as do many other behavioral addictions, which cause their sufferers to experience debilitating levels of dysfunction – many advances have been made toward better identifying features associated with it. Ongoing research continues to be conducted across the globe and mental health professionals are becoming increasingly cognizant of an all-too-easy-to mask issue that plagues a select segment of the population.

Bio:

Heather Hausenblas, Ph.D., is a physical activity and healthy aging expert, researcher, and author. She obtained her Doctorate from The University of Western Ontario, Canada. She was a faculty member and the Director of the Exercise Psychology Lab at the University of Florida from 1998 to 2012. She is currently an Associate Professor at Jacksonville University in the College of Health Sciences. Her research focuses on the psychological effects of health behaviors, in particular physical activity and diet, across the lifespan. She examines the effects of physical activity and diet on body image, mood, adherence, quality of life, and excessive exercise.

References

Costa, S., Hausenblas, H. A., Oliva, P., Cuzzocrea, F., & Larcan, R. (2014). Perceived parental psychological control and exercise dependence symptoms in competitive athletes. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.

Baekeland, F. (1970). Exercise deprivation: Sleep and psychological reactions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 22, 365–69.

Hausenblas, H. A., Gauvin, L. Downs, D. S., & Duley, A. (2008). Effects of abstinence from habitual involvement in regular exercise on feeling states: An ecological momentary assessment study. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13, 237 – 255.

Hausenblas, H. A., & Symons Downs, D. (2002). How much is too much? The development and validation of the Exercise Dependence Scale. Psychology & Health, 17, 387-404.

Mónok, K., Berczik, K., et al. (2012). Psychometric properties and concurrent validity of two exercise addiction measures: A Population Wide Study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13, 739–46,

Schreiber, K., & Hausenblas, H. A. (in press). The truth about exercise addiction: Understanding the dark side of thinsperation (228 pages). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub