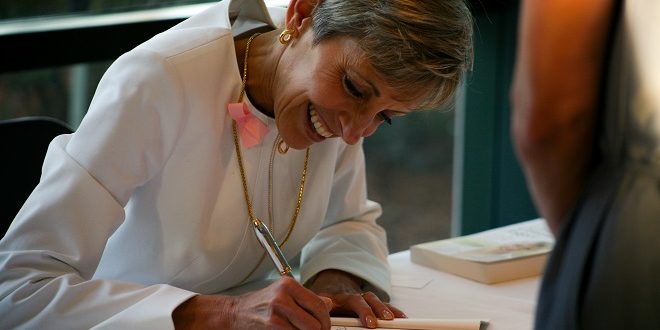

The Jacksonville University Brooks Rehabilitation College of Healthcare Sciences Distinguished Lecture Series recently hosted Trisha Meili, author of the best-selling memoir, I Am the Central Park Jogger. In an effort not to dilute the power of her presentation on October 24, 2018, in Terry Concert Hall, the transcript below is provided in lieu of our traditional format. The following has been edited for clarity.

Trisha Meili: FINDING RESILIENCE

I’d like to give another extra special thank you to Provost Sapienza who reached out to me and invited me, and your wonderful President Cost, who has been an enthusiastic supporter all along. The amazing leaders you have here really do help provide an exceptional educational experience, and I think Jacksonville is so fortunate that this University is filled with this caliber of leadership.

I’d like to give another extra special thank you to Provost Sapienza who reached out to me and invited me, and your wonderful President Cost, who has been an enthusiastic supporter all along. The amazing leaders you have here really do help provide an exceptional educational experience, and I think Jacksonville is so fortunate that this University is filled with this caliber of leadership.

For those of you at the Brooks Rehabilitation College of Healthcare Sciences, I really do admire your career choice because I know what a difference your work is going to make to so many, just as it made for me over the past 29 years.

I think wholeness is our goal, whether we’re recovering from trauma or trying to balance the emotional stresses of living. Wholeness is entirety, completeness, and free of disease. Healing is the process of moving toward wholeness. Healing isn’t becoming exactly the same as we once were. We move toward wholeness, certainly, through our physical health, but also through our emotional and spiritual health.

Every one of you, and especially those studying healthcare sciences, all along the continuum of care will be helping someone move toward wholeness. What I like to call the art and heart of healing.

[…]It was 29 years ago that I was living in New York City. I went for a run after work in Central Park and I was attacked. Investigators weren’t sure if my head fractures were from a lead pipe, a brick, or a rock. But I had been dragged into a wooded section of the Park, tied-up, gagged with my running clothes, beaten, raped, and left for dead. I laid in those woods for several hours until I was found, just by chance.

That night was a horrible one in the Park. Over 30 teenagers were roaming and doing what is called “wilding.” Eight other people were accosted or threatened in some way. This story really captured the headlines. Not only right there in New York City, but all over. People were wondering what this savagery said about our society.

As a result of that severe beating to my head on April 19, 1989, I suffered a traumatic brain injury which left me with extensive physical and cognitive dysfunction. After being brought to the Emergency Department, my temperature was only 85 degrees. I was hypothermic. My blood pressure was 70 systolic and there was no hearing or feeling diastolic. My left eye-socket had been crushed in, and the force of the blow had been so strong that a doctor later told me that my eyeball exploded through the thin plates of my orbital floor.

From the fractures, multiple lacerations, and damage across my face, I’d lost 75 percent of my blood, so I nearly bled to death. I was in a state of profound shock, or Class Four Hemorrhagic Shock. A priest was called in to administer last rites.

I was also in a deep, deep coma that lasted for 12 days. On the Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 points, I was given four points. As a frame of reference, that scale gives you three points just for being alive. Miraculously, I survived, and as a result of the brain injury, I have absolutely no memory of the events from the night of the attack. I actually don’t remember going running, the attack, being raped, or most of the time in acute care in Metropolitan Hospital.

Lesson No. 1: What We Feed the Psyche Matters

The first lesson learned from being in this horrendous condition is the importance of the messages I received—what was given to my psyche.

Thankfully, my family and close friends were with me through the entire ordeal. People from all over the world sent cards, letters, and even gifts. Children sent poems to me and some sent healing oil or holy water that my nurses rubbed on me. There was even a makeshift memorial put up in Central Park where people left fresh flowers and notes. And I got 18 roses from Frank Sinatra, which apparently made my mother really, really happy.

[excerpt read aloud from her book]“As for the cards, letters, phone messages, and presents, my family read and described them to me, even when I was hopeless. Pat was one of my nurses in the ICU. She held me in her arms and whispered of the support and told me of the gifts coming from around the world sent to comfort me and help me get better. Did I subliminally understand their words and gain strength from that unconscious knowledge? I’m sure of it, just as I am convinced that the cards and letters I eventually could read and understand were a vital factor in my rehabilitation.”

Of course, no recovery was possible without the enormous skill of the medical staff. But was there more? Didn’t I have thousands of friends working on my behalf? And I was hearing something else as well from the letters and cards: that I shouldn’t be ashamed. A common reaction among rape survivors is self-blame. It’s somehow my fault, a survivor imagines, and the internalization of that belief leads to shame, self-doubt, and silence.

Some survivors feel they must hide that they were raped, so the attacks go unreported. Well, secrecy was impossible for me. The whole world knew I had been raped, but to me, this was a benefit. “You shouldn’t feel ashamed,” the messages were saying. “We’re ashamed at how you were treated.”

People didn’t ostracize me because I’d been raped. Rather, they opened their hearts to me. It was so important for me to get these messages, especially early on, and I had an incredible example of this that I didn’t even know about until a couple of years after my book came out. I got an email completely out of the blue, and it’s such a powerful email that I’m going to read it to you.

[email read aloud]“I was the charge nurse of the Emergency Room at Metropolitan Hospital the night of your attack. I was one of the first to hold your hand and to tell you that you were safe and going to live. I remember every detail of that night as if it was yesterday. I held your hand until you left the Emergency Room for the ICU. I had only a small part of your care, yet I read your book as a proud father of one of his children who had gotten better after a long illness. I am honored to have known you, to have taken care of you, and to have fought for you. Thank you for enriching my life.”

I always have to take a deep breath after hearing those words. I don’t consciously remember him, those comforting words, or his holding my hand. But I do know that he had a profound effect on my unconscious body clinging to that thin thread of life that remained.

While I was in the coma, I was also getting the message that I was in charge. That I was an integral part of the recovery process. One of my nurses told me something many years later when I was doing some research for the book. [Pat] is this very, very strong woman from Jamaica who would hold me in her arms, whenever I became agitated, to calm me down.

One of the things she told me that really annoyed her was when physicians would come into my room and talk about my condition or my problems over my bed. She thought they should have gone to a conference room because she was concerned that I knew what they were saying. She told me, “You may not have been able to talk, but you could hear. There was nothing wrong with your ears, and besides, what’s the point of saying ‘she can’t,’ or ‘she’ll never,’ or ‘she won’t.'”

As soon as the physicians would leave my room, she would go to the head of my bed and say, “Don’t pay them any mind. What do they know? They’re only doctors. You’re a hero. You’re a trooper.” When I was able to talk, she would ask me, “Who’s the captain of this ship?” Apparently, I would answer, “I am,” and she would say I was absolutely right. “You’re the captain here and nobody else is the boss. You can do anything you want.” [Pat] was a powerful voice.

All of these messages of support that I received when I was conscious and unconscious, were confirmation to me that I wasn’t alone, I had done nothing wrong, I wasn’t to blame, and that I was responsible for my recovery. All of these messages gave me hope. In hindsight, I realize that was exactly what my psyche needed to hear.

Lesson No. 2: The Ability of the Body to Heal the Mind

Even with all of the support surrounding me, I remember a very frightening time in Metropolitan Hospital when I realized that something was very wrong. This was about six weeks after the fact, when I started to remember things and when hospital records no longer stated me as delirious.

One day a woman was sitting in my room and asking me questions. It turned out she was a neuropsychologist. I didn’t know she was a neuropsychologist then and apparently she had been there many times before. I remembered this particular session very well. She asked me to draw the face of a clock.

Now, I’d lost a lot of coordination in my hands and I tried to draw a circle as best as I could. Then I thought I’d be clever and space out the numbers as evenly as I could. It wasn’t a masterpiece, but I’d felt pretty good about what I had done. But then the real test began. She asked me to draw two o’clock and I froze. I could not remember which hand was longer, the hour hand or the minute. I thought, if I get this wrong, she’ll think I’m stupid. I felt so ashamed.

I felt scared and ashamed, of what I didn’t know and what I couldn’t do. Everything had been taken away from me. I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t think or speak clearly. I couldn’t even tell time. My condition was a threat to my mood, my level of self-confidence, and my sense of self-worth.

I spent about seven weeks in acute care at Metropolitan Hospital and then I was transferred to Gaylord Hospital in Connecticut for rehabilitation. I was there for about five months. One of the most memorable times at Gaylord was when I went running for the first time after the attack. A couple of weeks after I started to walk on my own without using a wheelchair, the head of the Physical Therapy Department, casually asked if I’d be interested in meeting with a group of people who got together on weekends to run.

[…]I thought it spontaneous, but it was part of my care plan. My treatment team—doctors, PTs, OTs, speech therapists, vocational therapists, recreational therapists—all met and talked about strategy for how to keep the progress going. At first, I was hesitant to accept the invitation. One Saturday morning, I joined them. There were four or five us there that day and I remember thinking if they can do this with each of their challenges, then so can I.

[…]It felt so good, like I’d conquered the world, and it filled me with such hope. I was taking something back and I had a big smile on my face. I felt good about my other successes, too, however small. This was a really strong motivator that kept me pushing to the edges of what was possible. What I learned was that the confidence gained in reaching a physical goal can be transferred to other aspects of rehabilitation or in life.

When we feel good about ourselves, almost anything is possible. Research shows that exercise is a tremendous motivator and self-esteem booster for those with brain injuries.

Lesson No. 3: The Power of the Present Moment

Paying attention really matters and all I can affect is the present. An example: I had lost a lot of the coordination in my hands and an exercise I did regularly to regain manual dexterity was something they called Put the Nail in the Hole. I was given a block of wood with holes drilled in it. Some holes were filled with nails and others were empty. My task was to take a pair of tweezers and transfer as many nails as I could from the filled holes to the empty holes in a given amount of time.

My OT stood there with a stopwatch and I did that exercise over and over again. First on my right hand, and of course, on my left. I did that exercise with such intensity that my mother once said that she couldn’t believe I did it with such concentration and patience. She told me it would have driven her crazy. But at that moment, I focused on what I could affect. The task right in front of me.

I didn’t get caught up in thinking about what had happened and a past I couldn’t change. Resentment about the attack didn’t grab hold of me. I didn’t entertain “what if” or “if only” and worked as hard as I could to make my reality as good as it could be. If I wanted to regain full use of my hands, wallowing in the past or worrying about the future was not going to help. The present moment was the right place to focus my energy. A day came when I was able to put on mascara again and with it came a real sense of accomplishment.

Before the attack, I’d never heard the term “present moment,” but as a result of my injuries, I found that I had to pay attention to my mind and body each moment because nothing came naturally.

When facing adversity, we often feel helpless and out of control, like we have no options. By working in the present moment, we can ask ourselves, “What can I do right now to make this situation better.” Just by asking that question, we regain control. We take responsibility and that can change a feeling of helplessness into hope.

Lesson No. 4: Learning to Accept Yourself Post-Trauma

One of the most difficult consequences of the attack is coming to terms with the deficits I suffered. I have lingering physical deficits even today, like no sense of smell, some double vision, and occasional problems with balance.

[…]Could I still meet the standards of achievement that were ingrained within me? Could I accept myself with these deficits? Would people take me seriously and listen to me?

In the spring of 2001, 12 years after the attack, I found the courage to finally face questions that I had run from. I decided to schedule another neuropsychological test at Gaylord.

[…]An example: West Wing. It was a great test for me to comprehend and follow all the different story lines, and they talked so darn fast on the show. But when a lot is going on at the same time, it’s difficult for me to prioritize and differentiate. So, mentally, I will never be the same as I was before my brain injury. Acknowledging that gives me peace and it’s a giant step in my healing. This is part of the woman I’ve become and most days, I like her.

Finishing Well

Finishing Well

More than six years after the attack, on the first Sunday in November of 1995, I ran the New York City Marathon. As I ran those last miles through Central Park, I felt the support from strangers cheering all of us on and proud of the hard work that had gotten me there. In that moment, I reclaimed my Park and knew I would finish well. I crossed that finish line after four and a half hours, with a huge smile on my face.

Healing didn’t mean becoming exactly the same as I was before, but coming to terms with what I had and what I didn’t have. For me, it’s a process.

With all the tremendous advances in the medical field we must remember that healing is also an art. The art of motivating someone. The art of seeing someone at their absolute worst and establishing trust. Melding those two aspects—the science and the art of healing—nurtures the human spirit.

Your love, support, care, and trust helps unleash a resource we all have deep inside that heals and helps us come to terms with our situation. From hope, possibilities will emerge. Each one of you has the power to play an important part in creating an environment that helps others move toward wholeness. The fact that I’m able to stand in front of you tonight is proof that the care you’ll give—the heart of healing—really does make a difference.

[END TRANSCRIPT]

Author of Bestselling Memoir I AM THE CENTRAL PARK JOGGER: A Story of Hope and Possibility, Trisha Meili’s story is about the capacity of the human body and spirit to heal. It is a story of hope and possibility. It didn’t begin that way. On April 19, 1989, Trisha went for a run in New York’s Central Park shortly after 9 PM. Hours later, two men wandering the park found her near death from a brutal beating and rape. In a coma, with 80 percent blood loss, a traumatic brain injury and severe exposure, doctors at Metropolitan Hospital worried that this young woman might not survive. The story seized the headlines, not only in New York City, but also around the world as people contemplated what the savagery of the attack said about our society. Trisha, known to the world as The Central Park Jogger, revealed her amazing story of survival and recovery fourteen years later in her best-selling memoir. Trisha now lives in Jacksonville, Florida, and serves as Chair of the Mayor’s Sexual Assault Advisory Council, and was Chair of the Best Practices Subcommittee to create the Sexual Assault Forensic Exam (SAFE) Program. She is also a survivor representative on Jacksonville’s Sexual Assault Kit Initiative and a member of the Steering Committee of Jacksonville’s Women’s Giving Alliance.

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub