When Jacksonville University’s female aviator team, the Flying Fins, placed 25th out of 55 teams in the Air Race Classic (ARC) last year, they were happy with their results.

After all, it was the first time the then two-woman team — Madi Bright and Rachel Chaput — flew in a race. Not to mention, inclement weather, which kept some teams from finishing, and some fierce competition made the race particularly challenging.

“Our goal last year was to finish the race and learn as much as we could because we were already planning to enter this year’s race,” Bright recalled. “Rachel and I were so excited that we finished in the top half.”

Being part of an elite community — only seven percent of licensed pilots are female — pushes you to improve. So with one race under their belts, the ladies aimed high, setting their sights on a top ten finish at this year’s race, which took place June 18-21. They added a third aviator to the team — Morgan Carney — and crushed their goal, soaring into fifth place.

“Not only were the Flying Fins fifth overall, the ladies were the fastest Cirrus aircraft and placed second among 16 collegiate teams,” Aviation Professor Ross Stephenson said proudly. “This is an awesome win for our team and JU.”

Flying in Amelia’s Footsteps

The ARC, a transcontinental speed competition with changing race routes each year, is the oldest women’s air race of its kind in the nation and is the epicenter of competitive aviation, drawing female aviators from all over the world.

The ARC continues the tradition of the first women’s air race, the Women’s Air Derby, flown by none other than aviation legends Amelia Earhart, Louise Thaden, and 18 other women.

“For these women it was not so much about the race itself, but about the opportunity to compete and prove they belonged in the air just as much as men,” Bright explained. “They knew what this would mean and what it would represent for future women pilots to come.”

This year’s ARC celebrated the 90th anniversary of that famous race from Santa Monica, CA to Cleveland, OH. JU has competed in the race since 2010.

“The race is one of the best real-world experiences for someone seeking a career in the aviation industry,” Bright said.

Being female is just the tip of the diversity scale in the ARC. Students, teachers, airline pilots, air traffic controllers, doctors, professionals, and business owners alike participate in the annual race.

You’ll also see different types of fixed-wing aircraft (from 145 to 570 horsepower) — #44 Flying Fins piloted a 2007 Cirrus SR20. And, as pioneering female aviator and storied Women’s Air Derby participant Blanche Noyes once said, “Flying is ageless” — the ARC draws pilots from 17 to 90-years-old.

The “Perfect” Cross-Country Race

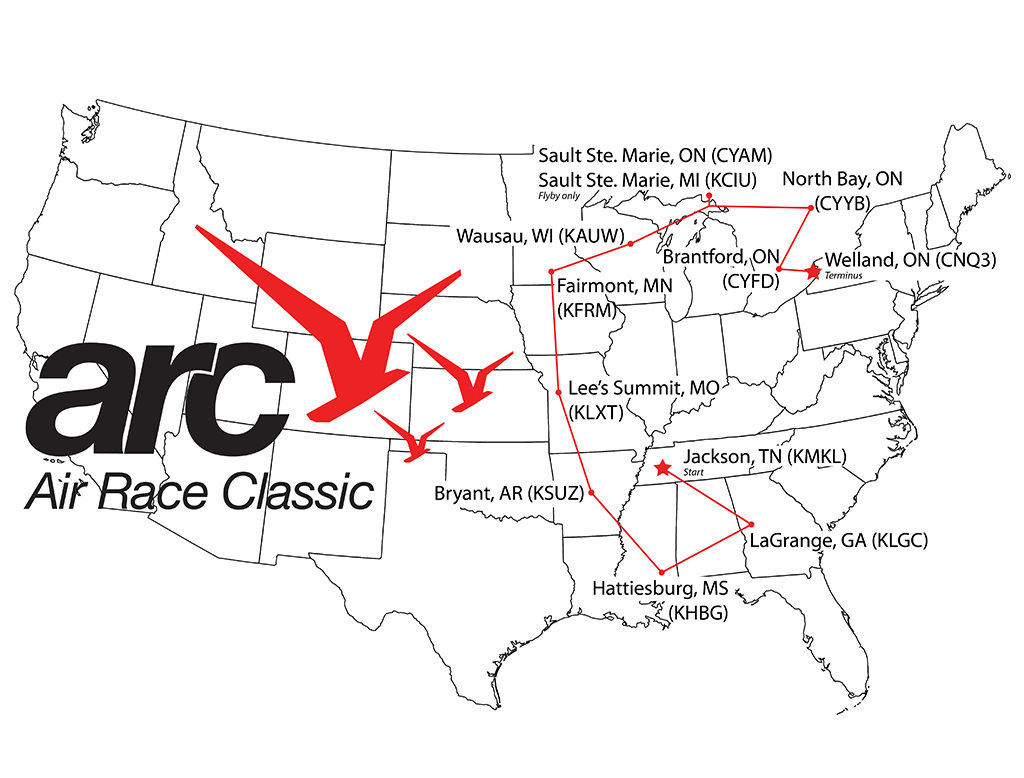

The ARC’s goal is straight-forward: teams of at least two pilots race approximately 2,400 statute miles in four days during daylight hours to reach the finish line. This year’s route began in Jackson, TN and ended in Welland, Ontario, Canada. Each year the route is chosen to present a variety of challenges to the racers, offering opportunities to learn and excel, while still within the endurance range of the slowest airplanes. The aviators experience changes in terrain, weather, winds, and airspace.

During those four days, teams must make flybys at eight or nine en-route timing points and then land at the terminus. The teams must also fly Visual Flight Rules (VFR) — one of two sets of rules created by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) under which a pilot operates an aircraft in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow her to see where the aircraft is going. Flying Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), the second set of FAA rules, in which the pilot navigates only by referencing the instruments in the aircraft cockpit, is not permitted.

“The race today allows all different kinds of airplanes to enter and compete in the same category, which seems unusual because different planes fly at different speeds,” said Bright. “In order to keep scoring fair, the score is based off of something called a handicap speed — a speed that is specific to the team, their weight, and their aircraft.”

The ARC committee calculates each team’s handicap speed during a handicap flight that is conducted in the months before the start of the race. “The ultimate goal is to be as much over your handicap speed as possible,” stressed Bright.

How the pilots beat their handicap speed is up to them. They are given the autonomy to play the elements, holding out for better weather and winds, for example. And this is where the true challenge of the ARC lies: how to design and execute the “perfect” cross-country journey.

Since the winner is the team that beats its handicap score the most, official standings cannot be released until the final plane has crossed the finish line. In fact, the last team to arrive at the terminus can be the winner. “We didn’t know where we stood until the next day at the awards ceremony,” recounted Bright.

Aspiring Aviator Gold

For more than 35 years, JU’s School of Aviation has been educating and training future professional pilots and aviation executives like Bright, Carney, and Chaput. Bright plans to work for the airlines after she graduates. What sets the school apart is its unique place in the Davis College of Business, which gives graduates both the aviation and business skills savvy employers are seeking. It’s also one of 36 universities in the nation selected by the FAA to educate future air traffic controllers under the Collegiate Training Initiative (CTI).

Additionally, the aviation program is now one of approximately 80 elite programs at colleges and universities whose graduates can qualify for a Restricted-Airline Transport Pilot (R-ATP) certificate with 1,000 flight hours versus the traditional requirement of 1,500 hours. The certificate allows a pilot to serve as a co-pilot until he or she obtains the necessary 1,500 for the Air Transport Pilot certificate.

“We are so thankful to the school, not only because of the education and experience we’ve received, but also for their help in securing a spot in the ARC,” gushed Bright. “Their generosity in helping us find a great financial donor, Carolyn Munro Wilson (Class of ‘69, ’77 and ’89), and an airplane from our partner flight school, L3 Airline Academy, was incredible. Without Miss Munro Wilson we never would have been able to make the trip.”

She hopes the Flying Fins’ recent win, along with JU’s participation in the ARC for nine years now, will draw future female pilots to the program and inspire current students working to get the flying hours needed to qualify for the race. One day soon, she’d love to see JU send two racing teams, like Auburn University.

“The whole race is really not about winning or losing, but about all the incredible women that get together once a year to fly across the country,” Bright emphasized.

For her and her teammates, that’s the real purpose of the race — the true sense of comeradery among these female aviators and the networking opportunities it provides.

“One of the pilots from the sixth place team is 90 years old!” exclaimed Bright . “This was her 18th race! She had the most incredible stories. And, many of the racers are part of The 99s [the international organization founded by Amelia Earhart that provides networking, mentoring, and flight scholarship opportunities to recreational and professional female pilots].” All that experience in one room is gold for an aspiring aviator.

“I can confidently say on behalf of Rachel, Morgan, and myself that we are so blessed to be a part of the Air Race Classic community,” said Bright. “It’s a community that, once you’re a part of it, will be with you for the rest of your flying career.”

By Thatiana Mejia Lott ‘94

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub