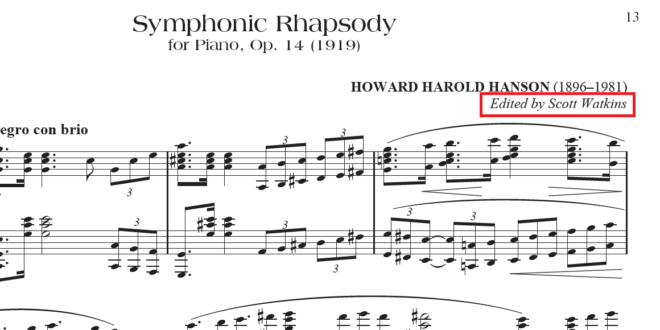

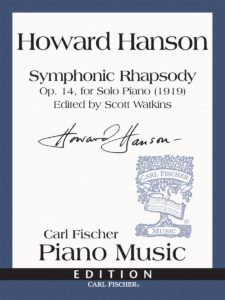

Worldwide sheet music publisher Carl Fischer Music now has a long-lost composition in its cache by award-winning American classical composer and music educator Howard Hanson, thanks to the “Indiana Jones”-type discovery and scholarly research of Dr. Scott Watkins, JU Associate Professor of Piano.

Watkins will perform the beautiful, dramatic “Symphonic Rhapsody, Op. 14, for Solo Piano” on campus for the first time March 9, which will be a recreation of the recital on which the work was premiered in 1919. Colleagues Benjamin Beck (piano), Jay Ivey (baritone) and Marguerite Richardson (violin) will also be featured at the concert, which will open with a solo organ work via video by Watkins’ former student, Jackson Merrill ’17.

“Symphonic Rhapsody,” which was thought lost to history, is Hanson’s largest single movement work for solo piano, at about 10 minutes. A remarkable finding by Watkins was that while it was believed to have been written originally as an orchestral work and then transcribed for solo piano, the piece was actually originally conceived and created for piano. Watkins, a longtime fan of Hanson’s music, played “Symphonic Rhapsody” at a performance in 2016 – the first time an audience heard it since Hanson himself performed it almost a century ago.

“This publication represents an exceptionally strong piece of scholarship by Dr. Watkins,” said College of Fine Arts Dean Dr. Henry Rinne. “He has performed the work on several occasions and has made scholarly presentations on it and the process of discovery. We are very proud of this accomplished faculty member and colleague.”

Watkins’ rigorous analysis and commentary means the sheet music he edited for the 145-year-old Carl Fischer Music will now be available to use in performance and education by students, teachers and virtuosos across the globe. Carl Fischer Music serves more than 1,400 retailers worldwide.

Wave Magazine Online talked with Watkins about the process of finding and editing Hanson’s work.

Can you tell us a little bit about what went into the process?

The manuscript is incredibly clean – by that I mean there are no erasures or deletions, and nothing was scratched out. It looked to me like it was ready for publication, but for whatever reason, Hanson did not pursue publication when he composed it. Minor things needed to be done like making sure that a group of notes actually contained the correct number. In another instance, Hanson created a chord with an obvious wrong note relative to the other notes in the chord. After a JU student, Daniel Farrell, and I went over it a few times, he made a computer-generated version ready for print. I approached the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., where Hanson taught from 1924 to 1964, seeking permission to submit for publication, which was granted. I then sent my materials to Hanson’s exclusive publisher, Carl Fischer, and they accepted. After a few minor adjustments to the score, the music was finally published.

How did you discover it, and what was your feeling when you did?

I and my wife, Dr. Marguerite Richardson (Associate Professor of Music), were at the Eastman School doing research on a book I am writing on Hanson’s early career. During my research I had learned that a famous Australian pianist and composer, Percy Grainger, had given a concert at the College of the Pacific where Hanson was teaching in 1920, and I had hopes of finding something from that concert. When I discovered a large folded cardboard poster of the concert, I was thrilled – but I wondered why the poster was folded and tied with string. The archivist at Eastman, David Peter Coppen, and I untied the string, and nine pages of Hanson’s unpublished manuscript – which had been thought to have been lost – literally fell out onto the table. I felt a bit like Indiana Jones! I was elated to have taken part in finding this lost manuscript.

From the time I found the manuscript to getting the work into print for public distribution took about a year. During this time, I was performing the work fairly often around the country and learned it from the composer’s manuscript.

What sets this piece apart?

Hanson’s “Symphonic Rhapsody” really fills a void in the canon of early 20th-century American piano repertoire. This work joins his small collection of solo piano works composed between 1917 and 1921 when he was on the faculty at the College of the Pacific. It’s unique in the repertoire in that it is, in the composer’s own words, “an attempt to put the emotional contents of an entire four-movement sonata into one movement of considerable length.” Hanson also said of the work: “Also, I believe that the material is the strongest that I have ever written, at least it seems to express more nearly what I am trying to say.” The premiere performance of the work took place in San Jose, Calif., with the composer at the piano on Oct. 27, 1919. In a review of his performance published the next day in the San Jose Mercury News, music critic Clarence Urmy wrote that the work “should be added to the repertoire of every advanced pianist.” I completely agree. Having performed the work a number of times across the country (with the permission of the Eastman School of Music), I can report that the audience reception has been very positive. I played it for the San Jose Woman’s Club May 23, 2017 – where Hanson himself last played it March 6, 1920. In the audience was 100-year-old Betty Ann Chandler, who, at age 3, was taken by her mother to attend Hanson’s performance! “My mother dragged me to everything,” she said.

How did this help you improve as an instructor and artist at JU?

Part of our teaching must include the encouragement of curiosity about the world around us. Had I not had the curiosity to seek some artifact related to that Percy Grainger concert in 1920, I might never have known about Hanson’s “Symphonic Rhapsody.” We must continue research into the unexplored and, as a university, we must embrace the role of repository for history in addition to the important work of preparing for the future. These are the concepts I and all of my colleagues at Jacksonville University work so hard to instill in our students.

What are the next steps for this?

I’ve lectured on this work in Vancouver for the College Music Society’s Pacific Northwest Regional conference and in San Antonio for CMS’s National conference, and for the Florida State Music Teacher’s Association in Orlando. In addition to the JU concert this spring, I’ve been invited to perform the work on a recital at the University of Nebraska in October 2018, and I lectured on and performed the work at TCU this past September. I plan to give the New York premiere of the work in October 2019, celebrating the work’s 100th anniversary. The next step is really an ongoing one: keep playing it.

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub