Although coral reefs in the Florida Keys aren’t what they once were, they remain beautiful and Dr. Dan McCarthy and his marine science classes are helping to further their restoration.

McCarthy, Professor of Biology and the Director of the Marine Science Center Undergraduate Program, travels with students at least once a quarter to near Summerland Key, about 20 miles east of Key West, to research and collect data that often is used in the courses he teaches.

”We are trying to help Mote Marine Laboratory, a non-profit institution from Sarasota that has a laboratory in Summerland,’’ McCarthy said. “One of the things they do is rear corals in the laboratory under optimal conditions where they grow more quickly than they would in the wild.’’

Once grown to optimal size, the transplants are then put on degraded reef areas.

“It’s an approach done worldwide except Mote is working on different kinds of coral that others are not,’’ McCarthy said. “Most of the coral restoration projects involve branching coral because they are easier to work with and grow faster. What Mote does is work on star and brain corals that are slower growing but more foundational. They have developed a technique that allows them to grow more quickly than normal.’’

McCarthy explains how Mote’s process works.

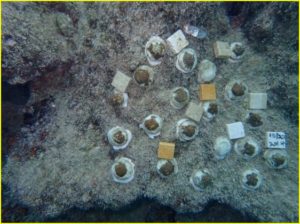

“They cut coral micro-fragments in their laboratory,’’ he said. “Out of one colony in the lab they can create multiple fragments in a relatively short period of time. They then place many fragments on dead coral mounts in hopes of re-skinning the dead mound with the tissue. They believe they restore a coral in about 20 years that would have taken 500 years to be formed. ’’

Further, transplants generally are from corals that are genetically more resilient to stresses such as extreme heat.

“Warmer water temperatures can result in coral bleaching,’’ McCarthy said. “When water is too warm, corals will expel the algae living in their tissues causing the coral to turn completely white but they can come back. Usually it’s not bleaching that kills coral directly but a pathogen comes in and kills.’’

“Warmer water temperatures can result in coral bleaching,’’ McCarthy said. “When water is too warm, corals will expel the algae living in their tissues causing the coral to turn completely white but they can come back. Usually it’s not bleaching that kills coral directly but a pathogen comes in and kills.’’

One of their challenges has been, at times, Mote’s corals die in the field and research indicates the mortality might be related to fish.

That’s where the JU effort comes in. McCarthy and his students have been working about two and a half years, both on site and in the classroom, in collaboration with Clemson University on how various fish, such as parrot fish, affect the reefs.

They are studying 12 reefs – six inshore and six offshore. The inshore reefs, about a mile from shore, generally are about 4-feet on the reef’s top and 12-feet on the neighboring sand. The offshore reefs are about 5 miles out, about 10 feet on top by 22 feet on neighboring sand.

“I’ve been surprised by the quality of inshore reefs,’’ McCarthy said. “Even though degraded compared to 30 years ago, they’re pretty nice reefs and must have really been wonderful reefs in the 1970s.

“One of the major suggestions on how coral reefs have degraded so significantly over time is through over fishing which ultimately affects the numbers of fish herbivores, like parrot fish, and reduce their numbers,’’ McCarthy explained. “Parrot fish serve a role; some are known to feed on algae that can cover over corals and/or out-compete corals for space. When you take out the parrot fish, the algae may grow unchecked. However, some parrot fish species feed directly on the corals so it depends on who you’re looking at. Some may hurt yet some may help the corals.’’

McCarthy said Mote has suspected some fish are feeding directly from the transplants.

“We’re trying to understand these herbivore, algae and coral interactions more,’’ he said. “Our collaborator Clemson University is studying similar interactions in the middle Keys while we’re working in the lower Keys. We are hoping to put our data together so we can say something more about the ecology of coral reefs through a larger area of the Florida Keys. While we are doing this we are trying to provide information to Mote on techniques to improve survival of their coral transplants.’’

The studies, funded from part of the money the state collects through the EPIC Program and the sale of Protect Our Reefs license plates, are important for a number of reasons.

“There is a high number of species, extreme biodiversity on coral reefs,’’ McCarthy said. “We need to preserve them for that alone.’’

And, of course, economic reasons play a part.

“There are entire industries built around the reefs,’’ he said. “You have fishing, diving … the entire ecotourism industry all have a stake in it.’’

– Jim Nasella

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub