Joe Johnson needed to feel the fear.

A JU Clinical and Mental Health Counseling masters student, Johnson spends much of his day with the chronically homeless as Housing Programs Manager for the local nonprofit Ability Housing, offering guidance on support services and finding housing for them.

But with his own built-in support system and a warm bed to go home to every night, he felt he couldn’t fully empathize with the homeless about what it really means to live on the streets.

So Johnson decided to live homeless for a couple days, sleeping outdoors, depending on nourishment from a food bank and spending his days in public spaces.

Finding one food supplier closed, missing out on a free blanket distribution, going long hours without sleep, avoiding arrest for trespassing and even hiding around a corner from a former violent client gave him a brief taste of just how frightening it can be to be alone and homeless.

“I learned some important things about myself doing this, but especially that empathy is going to be the foundation of my clinical practice as a mental health counselor,” said Johnson, who plans to graduate from JU’s program in the summer of 2018. “It’s impossible to build a therapeutic relationship if you can’t get into a person’s head or heart, and it’s difficult for clients to make progress toward mental health and wellness if they can’t trust others.

“This was a good way for me to get a little feeling for some of the very common experiences our people have had.”

Now, Johnson is using experience and knowledge gained on the job and through the JU School of Applied Health Sciences’ CMHC program to get closer to his clients and collect solid data for a pioneering statewide pilot study that is evaluating the cost-effectiveness of permanent supportive housing for the chronically homeless.

The three-year study, which began in 2015, is reviewing how costs and outcomes are affected in publicly funded systems of care when permanent supportive housing is provided to clients at three pilot sites in Duval, Miami-Dade and Pinellas counties.

Permanent supportive housing is described by study organizers as “the linkage of affordable housing with voluntary, person-centered support services,” and it is regarded as a best practice for helping the chronically homeless to permanently exit homelessness.

Duval’s pilot, called “The Solution that Saves,” is funded by grants of $150,000 from the Florida Blue Foundation, $120,000 from Disability Rights Florida, $50,000 from the Florida Housing Finance Corp. and additional money from other sources. The project is being overseen by Mike Cochran, Operations Director for Jacksonville’s Ability Housing, whose mission is to build strong communities where everyone has a home.

“This project is serving individuals who have been the most difficult to place and keep in housing in our community,” Cochran said. “Most of the Solution That Saves participants have been living on the streets of Jacksonville for a year or more and have severe chronic health conditions that put them at risk of dying on our city streets.”

Because Florida has no state-specific data to quantify the return on investment of providing stable housing, the findings of the statewide pilot are highly anticipated by safety net officials in the public and nonprofit sectors.

JU Clinical Mental Health Counseling Department Chair Dr. Sharon Wilburn and Dax Weaver, President of Health-Tech Consultants Inc., designed the Duval pilot study, are analyzing its collected data and then compiling official reports on it.

HTC’s 2016-17 interim report on the first-year results of the study, released this fall, found that providing permanent supportive housing for 58 of the 90 participants that had been housed at least one year at the time of the report brought down service costs by a whopping 50 percent, from $4,943,322 prior to being housed to $2,484,390 after housing.

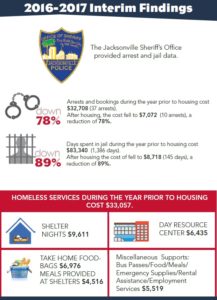

Arrests were down 78 percent; jail time plummeted 89 percent; homeless services costs such as shelter nights, meals, rental assistance and employment services declined 88 percent; and hospital costs dropped 63 percent, the report stated.

“The data clearly demonstrates that there is a meaningful decrease in costs if individuals are provided a stable home with appropriate supports,” according to the report.

Cochran, Weaver and Wilburn presented the findings in October at the Florida Supportive Housing Coalition’s annual statewide summit and again in November at the 2017 Florida Institute on Homelessness and Supportive Housing.

Johnson, meanwhile, was invited to present over the past year and a half at the Florida Behavioral Health Conference, the Florida Institute on Homelessness and Supportive Housing and the Florida Supportive Housing Coalition Summit. His topics included integrating peer support into supportive housing, housing navigation and location in supportive housing, and integrating substance use treatment and recovery into supportive housing.The Solution That Saves 2016-17 Report

JU’s 60-credit hour Clinical and Mental Health Counseling master’s degree, the region’s first with a flexible in-class/online hybrid-style approach, has been extremely beneficial to the 39-year-old Johnson as a nontraditional student, he said. The University’s faculty and academic format have been invaluable, he said, as he seeks to advance his career goal to create innovative approaches that help chronically homeless people with severe, persistent mental illness.

“Evert single professor I’ve had has been proficient, knowledgeable on specific topics and very supportive. That’s very helpful for people like me who are going back to school later,” Johnson said. “If I were trying to do this in a traditional model, I’d have to leave work early two or three times a week, and in my job I can’t do that. With the hybrid approach, I can stay up ‘til midnight online if I need to.”

The permanent supportive housing pilot study initiative was developed by Florida Housing Finance Corp. with input from representatives from the Agency for Health Care Administration and the Florida departments of Children and Families, Elder Affairs, Health, and Veterans Affairs.

The JU Master of Science in Clinical Mental Health Counseling in the School of Applied Health Sciences of the Brooks Rehabilitation College of Healthcare Sciences is a two-year, 60-credit hour degree program that meets the educational requirements for State of Florida licensure as a Licensed Mental Health Counselor and as a Marriage and Family Therapist. It is a full-time, cohort-model program based on best practice criteria and is practitioner-oriented. Students are also required to complete a rigorous 1,000-hour, community-based clinical field experience as part of their academic training. For more information on the program, visit https://www.ju.edu/mentalhealth.

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub