By Sheri Webber

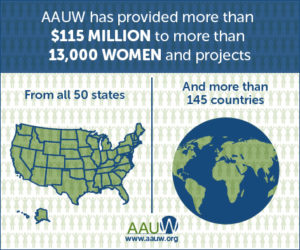

Empowering women since 1881, The American Association of University Women (AAUW) is one of America’s leading voices in promoting equity and education for women and girls. The AAUW 2018–19 academic year ushers in 250 women and community projects serving women and girls equaling $3.9 million.

Jacksonville University’s Alia Simon Montijo, a Chicago-based entrepreneur, pursuing her Master of Fine Arts in Choreography, is one of only 10 Florida students to receive an AAUW grant or fellowship. Montijo directly receives the maximum award of $12,000 through her career development grant to support her participation in JU’s low-residency MFA-Choreography program more than a thousand miles from her home and studio.

In the 2017-18 academic year, JU students Marcia Brito and Bamana Larsen were also recipients of AAUW career development grants, a distinction the University is proud to see students continue.

Montijo’s career has led to the development of two organizations—a professional dance company designed specifically to employ women, mothers, and minority voices and Dance Avondale, a studio serving children and teens who may not have otherwise had access to dance education.

Avondale is the community in Chicago where her studio is located, not the historic neighborhood with which Jacksonville residents are familiar. “That was like a sign from God when I was trying to figure out which school to attend. The only other Dance Avondale in the U.S. is located in Jacksonville,” Montijo says.

The MFA-Choreography degree program is a two-year low-residency program emphasizing pedagogy and the creative process. It is geared toward artists in a career transition or seeking career advancement. Applicants are required to have professional experience in the field prior to starting the program which begins with a seven-week Summer Intensive. During the non-residency portion of the program, students work remotely and continue their professional lives.

Accepting the Challenge

In addition to running a studio and serving as the founder of her professional dance company, Montijo is also a mother of three children under eight years old. She’s brutally honest about the challenge of earning a master’s degree while working and mothering full-time. “There is no glamour about it. Honestly, I spend most evenings at the dance studio, put my kids to bed by eight o’clock, and until about 11 or 12, I do coursework. And I try to do that every day. Sometimes I fail. Sometimes I do more. I haven’t figured out an exact balance yet, but I will.”

In addition to running a studio and serving as the founder of her professional dance company, Montijo is also a mother of three children under eight years old. She’s brutally honest about the challenge of earning a master’s degree while working and mothering full-time. “There is no glamour about it. Honestly, I spend most evenings at the dance studio, put my kids to bed by eight o’clock, and until about 11 or 12, I do coursework. And I try to do that every day. Sometimes I fail. Sometimes I do more. I haven’t figured out an exact balance yet, but I will.”

She sought JU’s MFA-Choreography program to feel inspired, provoked, and to grow as an artist. “I’m filling my mind with really provocative ideas that inform, inspire, and help me discover my roots as an artist,” she says.

Montijo gives much credit and gratitude to JU for such a unique program option, and also to AAUW, saying that a degree at this phase of her life just would not have been possible without serious support. “It’s such an honor to be a part of the AAUW legacy and I’m so grateful to be in alignment with the AAUW mission. As a feminist and a pretty progressive person, I’ve devoted my entire professional career to affording opportunities to women, like me, who are trying to balance raising a family and having a career.”

And “afford” is one of the key components to Dance Avondale and Mojito’s dance advocacy.

She explains that classical dance education upholds a hierarchical class or caste system because dance education is traditionally expensive. “Now, there’s validity to the expense. Dancers train their whole lives, go to college and continue training, and then enter professional dance careers that require them to make tremendous sacrifices. For me, that’s an accrued 25 years of experience. So, there is value in saying that I, as a teacher, am worth this amount of money.”

Tuition rates are one of the many ways that Dance Avondale, now in its second year, differs from other studios. “Through a partnership with the Chicago Parks District, I can rent a really big space, as opposed to owning a building, and that has allowed us to charge less than $3 per hour for instruction. For example, I’m currently teaching an 18-week class scheduled from September to December and the whole term costs $56.”

Relying on volume, her advocacy of equity in the arts then becomes doable. “The whole idea is this: if I can make dance accessible, the numbers will come. And they have. Our classes are overflowing, which means we’ve provided a resource the community wanted at a price they could afford.”

A Little Background

The youngest of five children who grew up in a working-class family, Montijo says she recognized the sacrifices made by her parents, Lebanese and Irish by heritage, to provide opportunities for her and her siblings. “I experienced privilege and opportunity because my parents sacrificed luxuries like new cars, vacations, and a house where everyone might have their own room. Through those sacrifices, they provided irreplaceable life experiences and opportunity. Everyone in our family sacrificed for one another in order to provide for each other.”

Dance Avondale, because of Montijo’s vision for her community, works to alleviate that deficit in opportunity.

Dance Avondale, because of Montijo’s vision for her community, works to alleviate that deficit in opportunity.

The neighborhood she serves is a working-class community, primarily Hispanic and predominantly comprised of family units. Montijo says, “On the Dance Avondale registration form, I don’t ask for demographic information, but I can tell you that we are a beautiful mixture of people and ethnic backgrounds. Incredibly diverse, and you can see that in our studio. The majority of my students speak two languages and their technical abilities vary. The oldest students are 14 years old.”

She says that, based on her own mixed heritage and as the mother of Latino children, she understands the significance of placing teachers representative of the community inside the classroom. “For my students, the teacher should be a reflection of their own diversity. That teacher is an affirmation for those families who believe that dance is only for a specific demographic. Children need to see people that look like them, whether in instructional or professional roles. This solidifies trust.”

“Children need to see people that look like them, whether in instructional or professional roles. This solidifies trust.”

The organization that most influenced AAUW in selecting Montijo as one of its 2018-19 scholars was Noumenon Dance Ensemble (NDE). The professional troupe is comprised of all adults with college degrees, all formally-trained in ballet, and exclusively female. As artistic director from 2015 to 2018, Montijo says she exercised a preference to hire women in their later 20’s and 30’s, as well as working mothers. “It’s a dance company for dancing mothers.”

Though it may seem silly to professionals in other industries, she says, to think that at 30 years old you’re in the latter part of your career and close to retirement, but in the world of dance, that’s the reality. More often than not, when professional dancers become pregnant, they retire. “After I became a mother and was asked to leave the company I was dancing with at that time, I decided to start a company that addressed this deficit. Just because we’re mothers doesn’t mean we lose our talent or passion. When dancers decide to have children, the time that is needed to devote to training, rehearsing, and performing can interfere with motherhood. Assuming that the answer is retirement is a narrative that must be changed.”

Though it may seem silly to professionals in other industries, she says, to think that at 30 years old you’re in the latter part of your career and close to retirement, but in the world of dance, that’s the reality. More often than not, when professional dancers become pregnant, they retire. “After I became a mother and was asked to leave the company I was dancing with at that time, I decided to start a company that addressed this deficit. Just because we’re mothers doesn’t mean we lose our talent or passion. When dancers decide to have children, the time that is needed to devote to training, rehearsing, and performing can interfere with motherhood. Assuming that the answer is retirement is a narrative that must be changed.”

Only in her second semester, Montijo says the winning combination of a low-residency, high-quality master’s program and the support of AAUW made the financial burden of earning a degree a possibility in her life. “It was instilled in me that humanitarianism, helping others, and the greater good is what life is all about. We all want to do everything we can for our kids and afford them every opportunity. I’m just trying to make that a little bit easier for minority and working-class families,” she says. “So, I feel like the privilege of this grant comes with a positive obligation to remind other women that there are resources and that goals like these are possible.”

For more details about the Jacksonville University College of Fine Arts and the Master of Fine Arts in Choreography program, please visit us online. For more information about Alia Simon Montijo’s work or Dance Avondale, please visit her online.

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub