By Sheri Webber

“What can I do? I want to help.” Those were the words of 22-year old Frances Bartlett to U.S. Representative Paul Cunningham in a 1939 letter. Cunningham had served during World War I and knew her family well. This offer of help, sent to his Congressional office, came from an ingrained desire to serve when all the world was marching into battle, something Fran had been taught growing up in Iowa.

She’d been told her eyesight was too poor to join the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), an auxiliary branch of the U. S. Army formed in 1942. As much as she wanted to enlist, she didn’t meet the physical requirements. Young Fran then set her sights on the War Department’s newly launched Army Hostess and Librarian Service program.

Both the USO and the Army Hostess program began to thrive, but Fran had not yet reached the mandatory minimum age of 25. Cunningham gently communicated this by letter and she promptly wrote back. “He was a friend of my parents, so I thought he would seriously consider my letter.” The mission of the USO was to help raise morale among troops and to provide wholesome diversions for the young men enlisted, most in their teen years and early twenties. She felt confident that she could successfully serve doughnuts, host dances, direct recreational activities, schedule guest entertainers and simply talk with troops before deployment whatever her age.

“Sometimes you just have to look for the opportunity,” she said later, and so her affiliation with the U.S. military began. Cunningham made an exception and Fran made herself indispensable during the following three years at Camp Crowder in Missouri.

Her time in Camp Crowder, corralling and entertaining approximately 70,000 troops that passed through, led to her becoming the Director of Recreation and Entertainment for the Veterans Administration in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was there she met Lt. Col. Harry Kinne, and they married shortly after. For a total of seven years, Army assignments would take them to the Asian and European theaters of post-WWII.

“My parents always taught me to be independent, and I had a general optimism about my own capacity to live unhampered by doubt, hesitation or fear.”

Still newlyweds, Fran and Harry were separated out of necessity while he responded to new orders. So she wrapped up the complicated business of a wedding and packing, all of it happening on an accelerated schedule. She later referred to that period of her life as “going round the world in four months.” She admits experiencing a few doubts aboard the USS General Blackford, a barracks ship decommissioned from military service about a year before her 26-day trip to China. “For a slight moment, I thought, ‘what am I doing here?’”

Crossing the Pacific

It was the autumn of 1948. Fran had left behind the well-decorated community receptions and finely dressed well-wishers hailing from Story City, Camp Crowder, Des Moines, Ft. Leavenworth, and many other places. She found herself along the 35th parallel, sailing directly from San Francisco to Yokohama, a distinctly Chinese settlement in Japan. As it turned out, the military-tanker-turned-ocean-liner had a piano in its main passenger lounge. “In the many days at sea, they kept me busy at the piano,” she said of her fellow passengers.

Yokohama, with its “hundreds of smokestacks which dotted the skyline,” she said, was her last stop before taking a ferry to the Chinese coast. The length of her trans-Pacific travels was only one of many obstacles she would repeatedly face while in Asia. After arriving in Yokohama, she received word that their intended home in Nanjing (or Nanking), China was inaccessible due to flooding of the Yangtze River.

“I said to myself, of course we would be happy. I had been taught that a person has two choices arising each morning—happy or sad.” The circumstances weren’t exactly what she had expected, but Fran was determined to make it work.

On October 2, 1948, Fran joined her husband in China’s huge port city of Shanghai, roughly mid-career for Harry. It took four long hours to dock in the busy East China Sea port. Not expecting to see so many people in such a compact area, she said of her nine days in Shanghai, “During that visit, I began to realize what a paradox is China.” Ancient yet refined culture juxtaposed with filth and extreme poverty.

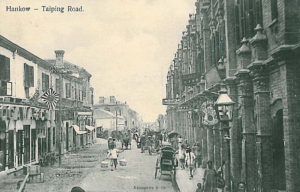

They were re-assigned from Nanjing to a city more inland, Hankow (or Hankou), and given the keys to a modest, three-room apartment on the second floor of a downtown building that also housed the Norwegian Consulate. She later wrote home about her early impressions and being surrounded by beggars, of all ages, as well as those who were more aggressive about extorting money from tourists and local shop owners.

On one shopping excursion with Harry, Fran tried to enter a shoe store, but could not for the “broad shoulders of a very bedraggled man” blocking the way. When Harry had the man move aside, it was easier to see the enormous snake in his hands. He was using it to threaten the shop owner. What he wanted was simple–hand over “cumshaw,” which is translated “bribe” in English, or the snake would be let loose in the shop. Fran watched the frightened merchant pay and the “snake man” move to the next shop.

During their brief stay in Hankow, Fran and Harry awaited the arrival of their furniture from the U.S. while living out of the two suitcases they were each permitted to carry on the long journey. Upon entering their residence, Fran and Harry discovered they had been assigned five servants. Never before had someone been employed in her service, or that of her family. She said it bordered on the ridiculous trying to find enough tasks to keep everyone busy within the sparsely furnished rooms. She likes to tell of the many opportunities they had to laugh together and appreciate the newness of an unfamiliar culture. “I still laugh at myself,” she says.

One of her “prize stories” from those weeks demonstrates her innate ability to find humor in any situation. It was their first night sleeping in the apartment. Among their few belongings, she had managed to pack a sheer, black nightgown. As a new bride, she thought it appropriate, and told Harry it was far more practical than the tennis racket he had brought. No sooner had they dressed for bed and slipped under the covers than a servant entered the darkened room, startling them both. The young boy carried an armload of stacked wood and went straight to the fireplace without saying a word. Fran stayed firmly tucked beneath the sheets. Soon a fire blazed and seconds later dozens of bats flew out of the fireplace in a fury of black wings and screeching.

Unbeknownst to Fran, Harry, and the boy, Japanese soldiers, who had recently occupied Hankow, stuffed chimneys all across the city as a last gesture of defiance. There was nowhere else for the creatures to go except into their bedroom where none of the windows had yet been pried open. “I screamed, pulling the sheet high over my head,” she said, “while Harry bounded out of bed and reached for the first thing he could find. In gales of laughter, I watched him wave that tennis racket dangerously, standing on our sagging mattress.”

Despite Fran’s own positive attitude, reconciliation with Chinese who had been under Japanese occupation often seemed an insurmountable task. Wartime inflation deepened, especially in a city like Hankow, and fear of Communist influence led to general suppression of everyday freedoms. The burnt shells of empty buildings and the presence of hungry children were physical reminders that war, both the Chinese civil wars and conflicts with Japan, had left irreparable damage in its wake. “All about us, in the ruins, were mushrooming tiny crude shelters which were being used to ease the housing crisis,” Fran later wrote.

“I was amazed to see the destruction left by the bombing during the last war.” She described in detail the flattened buildings, remnants of trenches, ruins and rubble, missing elevators and other evidence of past and ongoing warfare.

Not all brides chose to follow their husbands across the Pacific, but she did. Such a decision, though, was not without repercussions. “With hundreds of Chinese starving, it was difficult for me to eat,” Fran said of her temporary stay in Hankow. “All around me, I saw suffering and my reaction was a feeling of helplessness.” As a result, she became anemic and lost a significant amount of weight. With no American doctor available to treat her in Hankow, she was sent back to the capital city of Nanjing for medical attention, leaving Harry behind.

Trying to get back to Harry’s side after her hospitalization she found nearly impossible as the evacuation of all military personnel from that region of China had already begun. “With evidences of war all around us, it was disturbing to know that the city would have to withstand another onslaught,” she said. She was still in Nanjing, having received vitamin supplements and a thorough scolding from her American doctor about proper eating habits. Fran did not consider the ever-present option of returning stateside for further care because Harry was back in Hankow.

“With chaos everywhere, how was I to get to the airport?” During her brief treatments, Nanjing had been completely surrounded by Communist ground troops. “Buses, trains, and planes were booked with frantic men and women of all nationalities, and certainly no taxis were available,” she recalled. The U.S. military had ordered a mandatory evacuation. Complying with those orders meant flying straight from Nanjing to Japan, but Fran had other ideas.

“It was the wrong direction if I went back to Harry, but I was going to do it.” She had saved the calling card of a pilot friend whom she and Harry met days earlier, and remembered the friendly GI’s invitation to call any time. After explaining her predicament to the pilot, he urged her not to go back. But she insisted and finally he offered to fly her back into the interior if—and only if—she could get to the airport by 5 AM the next day.

Her next worry, as she later described in great detail, was how to get to the airport on time. So she attempted a trick she’d seen work for Harry. “I took a ten dollar bill from my purse, quickly tearing it into two parts. I handed one half to the driver, promising him I would give him the other half if he picked me up in time.” Now, she laughs at the recollection, acknowledging that it was likely illegal. She also recalls that, to her, it was as dangerous as it was frightening.

But it worked. The taxi showed up, the plane took off, and Fran arrived in Hankow in time to evacuate along with Harry and hundreds of other American GIs headed for Japan.

From China to Japan

“I will never forget,” she says, “the first day I was walking in downtown Tokyo. I heard music which seemed to come from everywhere.” It was “Tales from the Vienna Woods,” a waltz by Johann Strauss. She would soon begin teaching music and English at Tsuda College and a nearby public school for girls, both jobs for which she’d volunteered after getting settled into her new surroundings. Wandering the length of the street looking for the source of the sound, she located “large music boxes” on each corner. “Not having heard Western music for several months, it was a welcome sound,” she said. “It suddenly seemed very incongruous—Tokyo and Strauss—but music is the universal language of mankind.”

While in Japan, she worked with both men and women, the bulk of her teaching responsibilities in a classroom of girls, age 16 to 18. She had already taught music and literature in American elementary schools as early as 1939, and had a broad scope of experience directing school orchestra and band, playing trumpet and baritone, singing, and accompanying on piano, her primary instrument.

Fran and two of her students at the Girls’ School at Tsuda College in Tokyo.Over the course of those fleeting years, she had the opportunity to visit a pearl farm. She learned that farmers used a process developed by the Chinese before the thirteenth century involving three years of careful cultivating. “The idea of placing an irritant in an oyster to develop a pearl fascinated me,” she later wrote. “I often thought of this when I would face my students. Each one of them would become a wonderful pearl if I could just inspire them in the right way.” Decades later, a Des Moines columnist would write about her: “Kinne simply has the instinct of an oyster encountering a scratch of sand. When she comes upon a negative, she immediately begins to build a pearl around it.”

“I recall studying about Japan as a child,” she said. “And one of my most lasting impressions happened to be from a picture in my geography book—Fuji surrounded by blue sky and white clouds.”

Mt. Fuji, or Fuji-Yama as it was sometimes called during her time there, is considered sacred. For thousands of years, people have made pilgrimages there, ascending its heights, and it has always been actively promoted to tourists by the Japanese government. “Nothing is missed in publicizing the beauty of the volcanic mountain. Its likeness is seen on practically all souvenir items—jewelry, silk patterns and dozens of other articles sold everywhere,” Fran said in a letter to her uncle in February 1950. In that same letter, she asked him “Can you imagine trying to democratize 75 million people?” and began to think of the holy mountain as a symbol of the great task of repatriation.

She believed wholeheartedly that America had given hope and life to the nation of Japan. She wrote of Japan’s hopes regarding peace treaty talks in the same moment that she described the inspiring beauty of Fuji. She also admired Gen. MacArthur’s efforts in helping to rebuild the country post-war and spoke highly of him. “I took every opportunity to speak about the magic of democracy, too. Most importantly, I recognized that my own actions must be the prime example in support of democracy.” In trying to understand and practice this newly acquired form of government, her students imitated everything she did. She once confessed in another letter home that “I find myself scrutinizing my personal habits and speech constantly.”

Another object in Fran’s life that became a landmark representing the hardships, joys and lessons learned while in the Asian War Theater was Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. She sent home many photos of herself there, of its gardens, and of the many treasured moments she and Harry spent within the confines of the iconic building that still stands today.

“I’ll never forget the beautiful Peacock Room or the ballroom,” she said. It was where she would later meet the immensely popular wartime celebrity Bob Hope. The hotel was not only where she and Harry lived, but it also served as headquarters for Gen. MacArthur and his staff. The words she penned about the structure’s design, unwittingly, served as a comment on how she herself dealt with unforeseen challenges: “The hotel was purposely built to be flexible when earthquakes came. It worked.”

“Harry commanded the Allied Translator Service in General MacArthur’s headquarters, and there was no precedent for what he was to encounter in the repatriation of the Japanese prisoners of war,” Fran said. She was committed to helping him achieve that end and decided to assist the Japanese in re-establishing their schools, with no blueprint to follow.

So they both pioneered, moving toward progress and helping revive a nation. “Gen. MacArthur was great—a great leader,” she said of the man who personally tasked her with teaching English to a class of 50 Japanese policemen. These men were responsible for guiding traffic and performing other law enforcement duties throughout the country. Gen. MacArthur supplied her with 50 words to teach them, but Fran couldn’t resist adding one more to the list—democracy.

“I have always felt a deep sense of patriotism, but that same patriotism found new depth and meaning.” Fran also speaks of the Japanese Ministry of Education preparing an information guide to assist repatriates returning from Soviet-held territory, a pamphlet titled “Democratic Government and Non-Democratic Government.” Arriving POWs received copies from Harry and his colleagues. She and Harry worked side-by-side, five days a week, welcoming home tens of thousands of repatriated soldiers and developing a greater understanding of the nuances involved in colliding Japanese politics.

She often referred to the warfare in Asia and the Pacific, from the Chinese Civil War ending in 1937 up through World War II and, later, the Korean War, as a “battle for the mind.” When describing the atmosphere of Japanese POWs returning to the docks in Maizuru, she said, “Most of them had lost all ability for independent thought.” Her account includes men who were confused, terrified, demoralized and unable to let go of their forced loyalty to the Communist Party. Witnessing this firsthand, only solidified what Fran already believed. Positivity was a choice, and furthermore, that what a person believes to be true is as impactful as the truth itself.

As an Army wife, she considered reaching across racial barriers doubly important, and said much later in life, “If we could send enough students to foreign countries, and likewise host an equal number of foreign students in our country, we would be much less likely to have wars.” In 1951, Fran and Harry arrived back in the U.S., making a beeline to Walter Reed Hospital to treat Harry for Chinese Fever. After his recovery, they moved to Norfolk, Virginia, where Harry was assigned to the Armed Forces Staff College.

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub