It was 1969 – the final year of a decade marked by tragedy and riddled with change. Nixon was president, the country was embroiled in Vietnam, Woodstock invaded Max Yasgur’s dairy farm, and civil rights set the stage for what has become one of the most enduring and divisive issues in national history. Locally, long-held prejudices seemed to simmer in the sun. There were sit-ins and riots, but there was also a sense that something new was cresting, something that could broaden horizons and expand opportunities, something that brought a young Marvin Wells to Jacksonville University. It was the first non-segregated school he had ever attended.

He was nervous, trepidatious. He had never been around non-African American students before, never been taught by non-African American teachers before, never lived on his own before in a dorm room that he remembers as a veritable penthouse, compared to the childhood bedroom he shared with three brothers. Marvin Wells had never had access to the educational supplies that his previous school lacked, to the books and materials and equipment that were now afforded to him, but he did have one thing, a gift of sorts, instilled in him by mentors and role models, a character trait he would hone over the years and credit for his success. Marvin Wells had passion.

“Passion is my favorite attribute,” Wells said in a recent interview, conviction brimming in his voice. “If you have a passion for something, you can’t lose. You can compete in any theater of activity, at any level, because it is what drives you. Passion allows you to go beyond the limitations of your background or perceived ability. Passion allows you to have vision, to see what your natural eyes can’t. It’s the adrenaline which supercharges everything you do when used in coordination with preparation.”

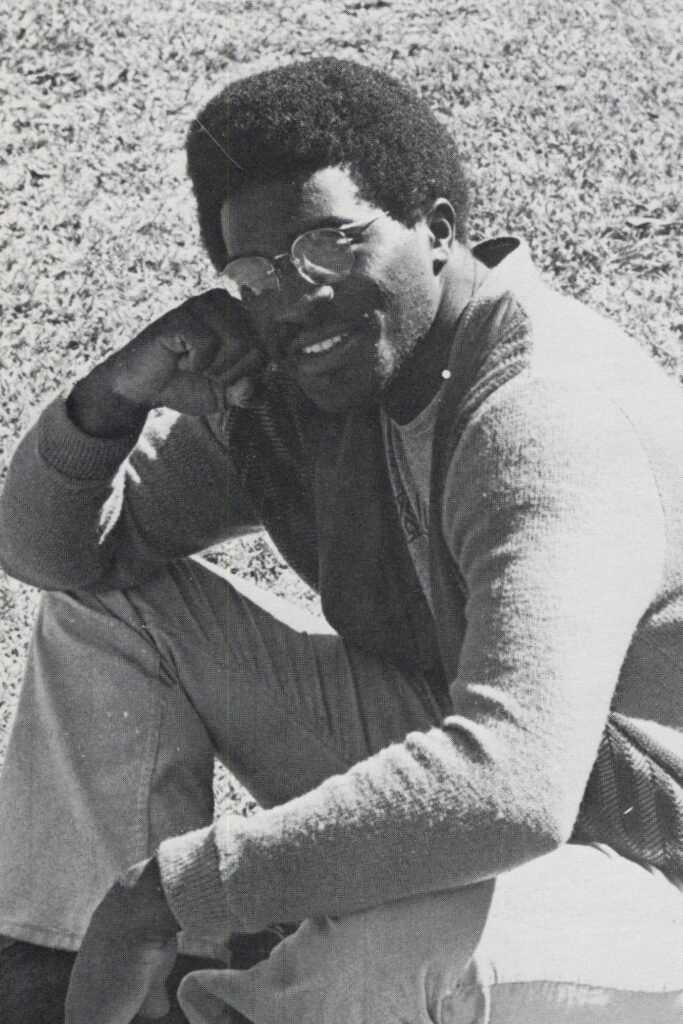

Wells wasn’t sure what would be waiting for him at JU, but for the most part, he was pleasantly surprised. His fellow students were receptive, and they seemed genuine. His professors treated him the same as everyone else and encouraged him to grow and excel based on his own merits. They didn’t stay locked in some ivory tower. They were approachable. Many of them interacted regularly with the students on campus. Wells was shocked to see them shooting hoops at the basketball court and even more astonished when professors Ted Allen and Bill Robinson, encouraged by Dean of Students Wayne Corbin, agreed to form a basketball team with Wells and a friend. According to Wells, their intramural games were legendary, often played to large crowds, in a manner reminiscent of the March Madness that surrounded the school’s appearance in the 1970 NCAA Championship.

For Wells, JU was becoming a home away from home, the people he met, a family. One day dissolved happily into the next, and campus became a haven of sorts.

“There were still racial challenges going on in the community,” Wells said. “We were still reeling from the memory of Axe Handle Saturday 1960. There was still a lot of discrimination. There was still busing. I had graduated from a segregated school system. All of those things were still happening, but inside of campus, it wasn’t that way. I had walked into an environment within the city of Jacksonville that was very different from the Jacksonville I was accustomed to.”

That’s not to say there weren’t challenges. Wells arrived at the university with a stutter and was embarrassed to speak up because of it. In class, he preferred to blend into the background, never raising his hand, dreading the prospect of having to answer or recite anything. It was a strategy that worked well until the day that changed his life forever.

Wells smiled at the memory. He was in his first-year English class, in a room with over 100 students, and he had a question – not just any question – but a burning question he had to ask that day. His strategy: wait until after class, until all the other students had left, and then approach the professor. Her name was Katherine Phillips, a transplant from the northeast. She looked at him and then down at her grade book as she had done with the other students, then back at him as if every preconceived notion she had ever had was being tested at that very moment. Wells had an “A” average in her class.

“Walk with me,” she said, and so began a relationship of mutual respect. Philips wanted to know how Wells came to JU, why he wasn’t in a northern school, what it was like growing up in the Jim Crow South, if he had any current concerns. Wells walked with her on a regular basis, sharing his experiences and eventually confiding how his stutter had impacted his confidence. Phillips took this in, then asked him to meet her in a classroom in the science building for a few hours that Saturday and every Saturday after that. She had a stack of books for him to read into a tape recorder, and little by little, book by book, they tackled his stutter.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Wells said. “And then she threw the gauntlet at me. She said, ‘You can do anything you want to do. You do not have to be ashamed or intimidated. Continue to read, seek speaking opportunities and use this newfound gift that you have.’”

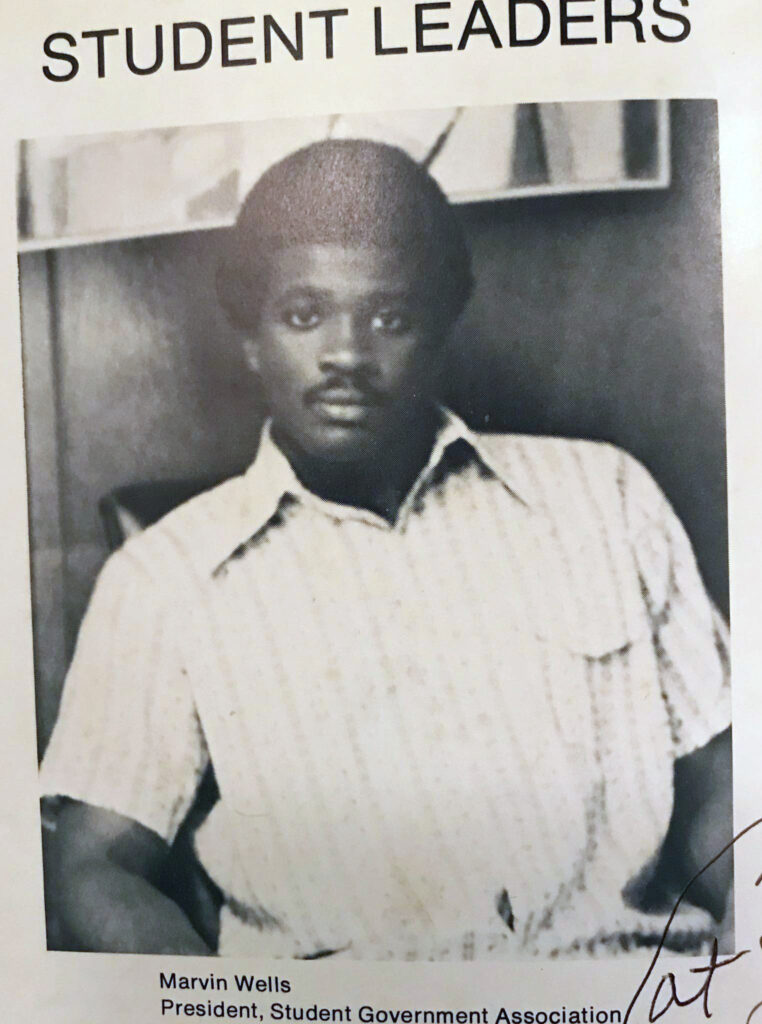

Having overcome one of the giants in his life, Wells did just that. He started debating, got involved in student government, ran for office, and ultimately ran for and was elected student body president. He was the first junior and the first African American in school history to hold the position. One of his biggest fans at the time is a name well-known to the Dolphin family – Dr. Frances Kinne. As Florida’s first female university president, Kinne may have had something in common with Wells. She was a treasured friend to students, faculty and staff, and served the university for 62 years before her passing in 2020.

“She adopted me as her own after my sophomore year,” Wells remembered fondly. “She got me involved in everything, made sure I was involved in fine arts and on committees. She was just an incredible facilitator and an incredible lady. We kept in touch over the years. We talked a lot. I can never forget her. I miss her.”

Wells graduated from JU in 1973. He went on to graduate with honors from dental school at the University of Florida before going to Downstate Medical School/Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, N.Y., for his residency.

Confident that he received “the best training in the world,” Wells – now a newly minted maxillofacial surgeon — felt as though there was nothing he couldn’t accomplish in his profession. He was also enjoying a new level of acceptance.

New York was not the segregated South. He didn’t have to keep to one side of town, wasn’t looked at sideways whenever he entered a store. That made a powerful impression on him, and he decided to stay. In fact, he had no intention of returning to Jacksonville, and then, his mom called him home.

“How could I say ‘no,’” Wells stated without the slightest hint of regret. “I owed her too much. It’s not that I wanted to come back, but she asked, and I complied.”

Upon his return, Wells ran into several roadblocks. Banks refused to loan him money, fellow white dentists cancelled meetings with him, and hospitals denied him certain privileges.

After a year of trying to establish his practice, Wells had no patients, escalating bills and minimal reception within his professional community, but he didn’t give up. His older sister bought him a new suit. He sat in emergency rooms at night, hoping to catch a break, and called every one of his colleagues every weekend to see if they needed emergency coverage. In June of 1981, someone finally said yes.

Wells was called for two emergencies that weekend. He wore his suit to make a good impression. He used the advanced techniques he had learned during his residency at Downstate Medical School, and he did what he had been trained to do. He took care of his patients. He used his talent, and word – at last — began to spread.

Today, Dr. Marvin Wells is a successful oral and maxillofacial surgeon and owner of the Wells Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Association with locations in Jacksonville and St. Augustine. He has worked hard for his accomplishments and faced adversity because of his race, but he refuses to dwell on this.

“Everyone has challenges,” he maintained. “We all have issues. The biggest blight by far in our country is the nearly 400-year denial of equality of opportunity, basic human rights, dignity, education and access because of the color of your skin. There are immigrants coming into our country every day with virtually nothing, and what they want is similar to what I wanted when I first came to JU. We want to have the chance to compete, to grow on our own. We just want to have the equality of opportunity. That’s really what it’s all about. I don’t want you to do anything special. Just give me an equal opportunity to succeed.”

According to Wells, giving ALL people the same chance is what society must do. As for individuals, “What you must do is never give up. Dream! Look beyond your circumstances, look beyond what others tell you. Don’t allow others’ negativity about you to have free rent in your head. If you never allow yourself to surrender to complacency or defeat, then you can make it.”

Jacksonville University’s Homecoming & Family Weekend, 2019

Wells is living proof of that. He is still practicing in his profession. He is active in his church, where he serves as a deacon and married ministry leader with his wife, Nicole. He is devoted to his faith and, of course, to Jacksonville University.

Wells has tremendous respect for the passion and vision of current Jacksonville University President Tim Cost. He has served on the board of trustees and is a current member of the Brooks Rehabilitation College of Healthcare Sciences advisory board. He is also a member of the Black Alumni Network and was one of the first contributors to the Black Alumni Scholarship Fund, which he describes as a “rescue basket” for students who might not otherwise be able to attend JU — students like him.

While not common knowledge, Wells was accepted to every school to which he applied, including several Ivies. He chose Jacksonville University primarily because of the scholarship and aid package it afforded him. The fact that the university was willing to take a chance on a kid from William M. Raines High School on the north side of Jacksonville still means a great deal.

“It’s been more than 50 years since I began at JU as a student,” Wells said with an incredulous shake of his head. The figure seems to resonate for a moment, the nostalgia palpable, because in so many ways he’s still there. In his heart, he is still that young man on campus, being helped and encouraged in ways he could never imagine, playing basketball with his teachers, kicking back in his dorm room, learning and striving and thriving. The memories live large in his life. He is grateful for the kindness he was shown, the equality he was given, for the glory days that set him on his way – not just with a diploma – but with the firmly established sense that he could soar as high as anyone else.

By Jacqueline Palsha

Director of Communications

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub