You’d think it would be impossible to breathe in 28.8-degree water, much less re-breathe.

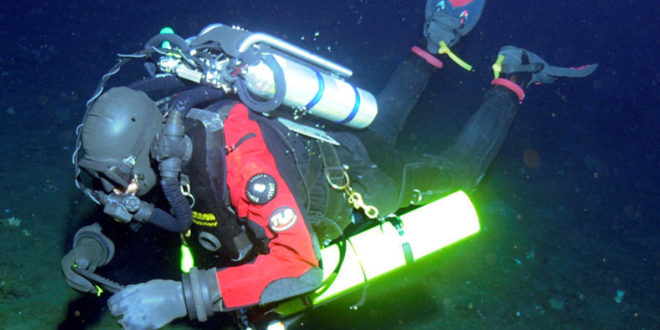

But that’s just what divers are doing in the unthinkably icy Antarctic with the help of rebreathers, special equipment that is the focus of a critical study led by Research Scientist John Heine with the JU Marine Science Research Institute.

The evaluation is being completed this month at McMurdo Station for the U.S. Antarctic Scientific Diving Program, with the aid of a $58,000 National Science Foundation grant won by principal investigator Heine and JU. It will test whether rebreathing equipment, which scrubs and recirculates divers’ own carbon dioxide for use again during a dive, can operate safely in such frigid waters.

Results of the research “will have a far-reaching impact in the scientific diving community, and potentially benefit polar scientific diving as a whole,” Heine said, as new frontiers in polar scientific research will open if rebreathers are found safe and effective in the frigid conditions.

“They have been used for scientific diving in other environments, and we wanted to see if they would function adequately for use in this harsh environment,” said Heine, who is also an NSF USAP Diving Safety Officer.

Over 25 years and with various research outfits, Heine has been one of only a handful of diving supervisors worldwide for Antarctic scientists. His work supports the United States Antarctic Program and the National Science Foundation’s Division of Polar Programs, among others.

“We are proud to have John Heine associated with Jacksonville University and the Marine Science Research Institute,” said Dr. Lee Ann Clements, Associate Provost and Interim Dean of the College of Arts and Science. “This study in particular is important for research diving overall and especially for the sensitive environments in the Antarctic.”

The potential scientific uses for rebreathers in the cold depths of the Antarctic include behavioral studies, under-ice collections and sampling, use in the McMurdo Dry Valley lakes to minimize mixing of water layers and the addition of higher volumes of exhaled gases to the environment, and extended range (time and depth) underwater.

Rebreather systems are nearly silent underwater and emit few bubbles, with the exhaled gas held in a closed loop and reused by the diver after carbon dioxide is scrubbed out and oxygen added. Their use in warmer waters has been steadily increasing in recreational and scientific diving communities over the past decade.

Rebreather systems are nearly silent underwater and emit few bubbles, with the exhaled gas held in a closed loop and reused by the diver after carbon dioxide is scrubbed out and oxygen added. Their use in warmer waters has been steadily increasing in recreational and scientific diving communities over the past decade.

Test results using the rebreathers in the Antarctic so far look positive, Heine said.

“Generally they’ve been going pretty well,” he told The Antarctic Sun. “We’ve had a few little alarm issues and things like that that are easily dealt with.”

They have a number of advantages over “open-circuit” scuba systems, one of which is lessening the disruption to wildlife and the environment.

“[Rebreathers] don’t emit bubbles, so the animals’ behaviors have less of a tendency to change,” Jeffrey Bozanic, a leading rebreather expert on the project, told The Antarctic Sun newspaper. “A lot of animals that you would never see while on open circuit you’ll see on rebreathers.”

In addition, under the frozen surface of the McMurdo Dry Valley lakes, the water has many layers with varying temperatures, salinity and water chemistry. Using rebreathers that decrease exhaled air bubbles keeps the layers from mixing and disrupting microorganisms in the waters.

Dive team members have been testing six different rebreather systems to see how they perform in the freezing conditions, stressing them with rapid temperature changes and leaving them in sub-zero air to document how they respond.

In the meantime, scientists and divers await the results.

“They will be released as soon as we can work them up,” Heine said. “We plan to give talks at conferences on it next year as well.”

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub

Wave Magazine Online Jacksonville University News Hub